Are you surprised by your own ability? You might be a victim of the Dunning-Kruger effect

What it is, how it works and how to run away from it!

Have you ever met someone who’s extremely bad at something but doesn’t seem to be aware of it? It turns out that person might have fallen victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect.

The cognitive bias was first identified by psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger in a 1999 study.

Their paper, entitled Unskilled and Unaware of It, summarized, "People tend to hold overly favorable views of their abilities in many social and intellectual domains."

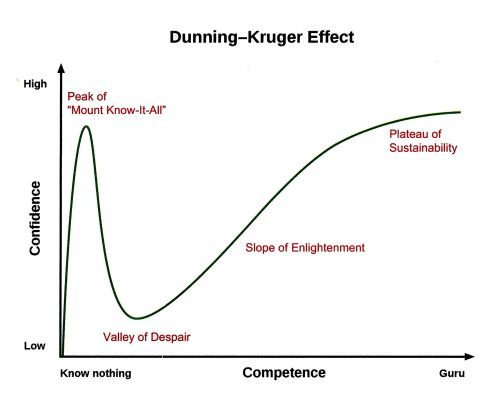

In short, the Dunning-Kruger effect occurs when a person’s lack of knowledge and skills in a certain area cause them to overestimate their own competence. By contrast, this effect also causes those who excel in a given area to think the task is simple for everyone, and underestimate their relative abilities as well.

Source: IEEE Pulse

Imagine you and your friends decide to try something new—separately, you all start learning French. Within a few days, you can say 10-15 sentences. You’re a bit disappointed, and believe you should be able to say more by now. To you, the language is quite simple, but having a good grip on it causes you to think it is simple for everyone, and that you therefore should have done more.

Your friend, by contrast, has learned just a few words. He is amazed by his progress. He doesn’t yet have the knowledge and skills to know that he’s actually pronouncing those words wrong, and forming grammatically incorrect sentences with them.

He’s learned the least in the group, but his lack of knowledge prevents him from understanding his own mistakes. Moreover, his lack of access to comparison causes him to overestimate his relative ability. His ignorance of how far others, like yourself, have come, keeps him thinking he’s excelling, when he is actually learning at below-average speed.

As a result of the Dunning-Kruger effect, you may not know what you’re good at, because you assume that what comes easily to you also comes easily to everyone else. You are therefore robbed of the ability to spot your own specialties and talents.

Moreover, when you excel at what is challenging to you, you might accidentally fall prey to the belief that that thing is where your talents lie. In reality, you may just be a below-average performer finally approaching average levels.

In short, the Dunning-Kruger effect states that the very same skills that are needed to excel at something are also needed to recognize ability in that same field.

We can apply this effect across different domains: the markets, business, sports…anything. We’ve all had that one boss - the know-it-all who actually knows very little.

These bosses (who typically get stuck in middle management) hold back organizations from high performance. They are easy to spot - we all know who they are. Beware this boss!

An effect with serious consequences

As a society, we miss learning from the best of the best, because their confidence keeps them behind closed doors. At centre stage, all too often, can be people of below-average capabilities.

Unfortunately, those who are the most ignorant—in the bottom 25% of any skill—also overestimate themselves the most. In the context of our democracy, this means our most uninformed citizens are also our most confident ones. Not only are these ignorant people extremely resistant to being taught—since they believe they know the most—they are also guilty of sharing the most information (read: misinformation).

At its core, the Dunning-Kruger effect preys on just that: not a lack of information, but rather an abundance of misinformation. We know when we know nothing, but it is information that is wrong that causes us to think we know everything, and absentmindedly press “share.”

On a national or global level, this effect has dangerous consequences that we’ve already seen in action. In essence, if you are a politician, you may actually benefit from having a more uneducated audience. People who know less about political and world issues are more likely to believe what you say, consider themselves well-informed, go out and vote, and share your views with others.

Those in the upper to middle of the pack—somewhat informed about political issues—are more likely to disengage from political discussion and avoid voting, because they don’t believe themselves to be worthy contributors. While experts—the most informed of all—know they have a strong knowledge base, but they avoid educating the public, simply because they don’t realize the rarity of their experience.

Our society’s disease of self-awareness causes ignorant and misinformed people to have the confidence to claim the microphone, while experts and well-informed folks are behind the stage, rolling up the curtains. This phenomenon spreads misinformation and ill-informed views throughout our social worlds, causing us to miss real learning opportunities we could gain from one another.

If too many ill-informed people think they are the best, our society is left with many growing fish in a tiny, shrinking pond.

Why does this actually happen?

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a bit of a Catch 22. People who don’t know much about a subject don’t have the knowledge or skills to spot their own mistakes or knowledge gaps. Because of these blind spots, they can’t see where they’re going wrong, and they therefore assume they’re doing great.

On the contrary, people who are at the top of their game in a certain subject area don’t have the ability to notice their specialty, because their work comes so naturally to them that they don’t realize it’s not this way for everyone. The ease with which they pick up these skills or knowledge areas blinds them to the fact that the work is more challenging for others. Rather than underestimating themselves, they overestimate that everyone else’s abilities match their own.

“Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge.”

—Charles Darwin

Although the effect has been found to occur in fields and subject matters as diverse as emotional intelligence, logical reasoning, financial knowledge, political informity, chess, driving, and even medical knowledge, there is recent doubt about its accuracy as a bias of the human brain. Research from 2016, cited in this article, suggests that since computer generated data are also subject to the effects of Dunning-Kruger, it is a computational phenomenon, and thus cannot count as a bias of the human mind.

But how can we make sure we don’t fall victims of this very same effect? After all, if everyone is prone to this cognitive bias, it means you and I could also be THAT person!

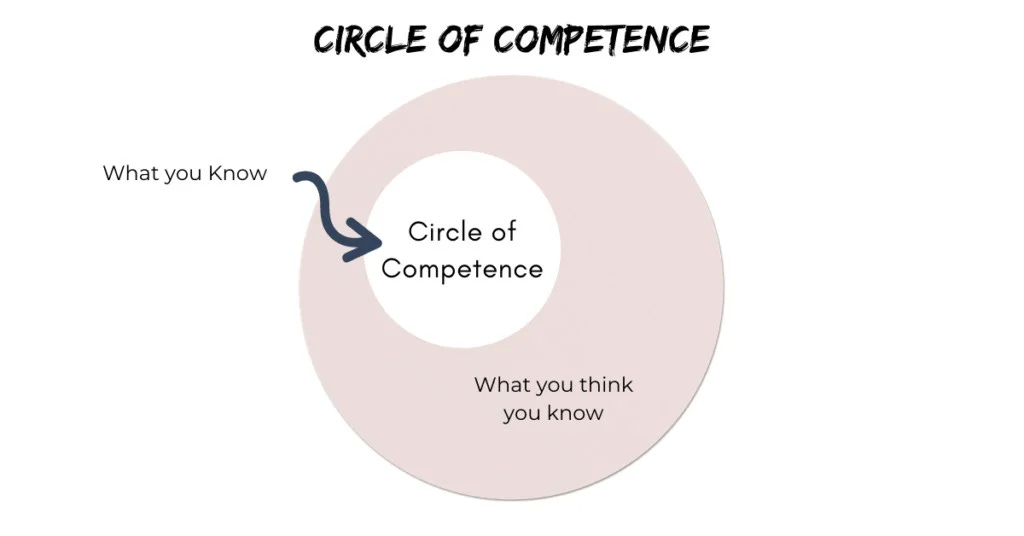

The first step would be to try and identify your Circle of Competence. Essentially, this is the set of topic areas that align with a person's expertise. Be ruthless in identifying and protecting the boundaries of your Circle of Competence. Sorry to break this to you all: it's usually smaller than you think.

Source: Wise.com

The key here is not so much knowing what you know, but rather knowing what you don’t know. As Charlie Munger once said: "avoiding stupidity is easier than seeking brilliance”. Know what you don’t know and steer away from it.

Over time, work to expand that circle but never fool yourself about where it stands today, and never be afraid to say “I don’t know.” Change that. Know your competencies, focus on them. Know your incompetencies, avoid (or outsource) them.

The next time you catch yourself marveling at your skill at a task, remember the Dunning-Kruger Effect and the strategies for avoiding it. Don’t be that person.